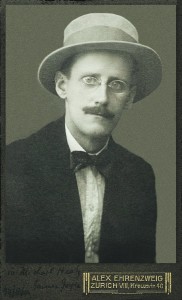

Author James Joyce.

Today, 16th June, is part of the ‘Church Calendar’ for those who are into Irish literature. It is Bloomsday, the day on which the fictional character Leopold Bloom takes his ‘odyssey’ around Dublin in James Joyce’s extraordinary epoch-shaping novel, Ulysses. Joyce’s 1922 book is a splendidly experimental, hilarious and cryptic reworking of Homer’s Odyssey. Where Homer roamed the earth on his epic voyage, the anti-heroic Leopold roams the streets, pubs, brothels and churches of Dublin in just one day (across 800 pages of scintillating but demanding writing).

James Joyce sums up much of the modern era of artistic endeavour. His writing is a wrestle between authority and freedom, reality and imagination, conformity and sensual play. In Ulysses, he toys with the seriousness of history by reconstructing it within the apparent silliness and unimportance of one man’s day about Dublin. No big epic, just little domestic duties, he seems to say. No large story (like the one the Bible tells), just small, individual tales.

The impulse behind this comedy is in fact a deeply serious one. Joyce was distressed about God, death, love and relationships, and his writing is a response to that distress. We see this in numerous places in his novels and stories, as well as his sometimes torrid personal correspondence.

“How I hate God and death! How I like Nora!” Joyce wrote as a young man who was angry with religion and with mortality, and longed for deep, intimate connection with another human being – his future wife, Nora. His rebellious spirit might just be dismissed as raging youthful hormones. Or it could be condemned as opposition to the things of the Spirit in loud favour of the flesh.

But perhaps there is a more sympathetic and productive view of what it is for which Joyce is crying out.

Joyce’s assault on traditional religion and his ridicule of the church were accompanied by a longing for deep, interpersonal connection, freedom, love and lasting meaning.

The fictional Leopold “Poldy” Bloom for whom Bloomsday is held in recognition.

It’s a combination of desires that we find only too often in not just writers and artists, but in so many average Aussies today.

In Joyce’s Ireland, the Church was (rightly or wrongly) associated with suppression, control, and inhumaneness. From the kinds of newspaper headlines and Facebook posts that I currently read on a daily basis, attitudes to churches in Australia (rightly or wrongly) aren’t so different.

Some of Joyce’s, and today’s Australian’s, frustration might be relieved by a more biblical, less ‘churchy’ and institutional, understanding of the Christian faith. When Christianity is all about restriction, conformity and institutions, it generates resentment in those affected or simply looking on.

Instead, when Christianity is primarily about our relationship with God; when it celebrates the peace, grace, joy and goodness on offer in this life; when it is understood to be an advocate of good food, good friends, good fun and even good sex; then, the disgruntled Joyces start to pay attention again.

When Christian faith is cast in its positive light, as a gift of the God who “so loved the world”, it is more likely to be celebrated. It is about God befriending sinners, best demonstrated through the example of Jesus. It’s about God’s love for us, even as we hate him – a teaching that even the most sensually driven of characters needs to take seriously. It’s joy, not killjoy. It’s cause to rejoice, Joyce.

On 16th June each year, I like to read a little from Ulysses, have a good meal, and then thank God for his great big ‘Yes’ to us in Christ which gives such lasting pleasure when compared with the bawdy ‘yes’ that ends Joyce’s novel.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?