Remembering Malcolm Fraser: excerpt from ‘In God They Trust?’

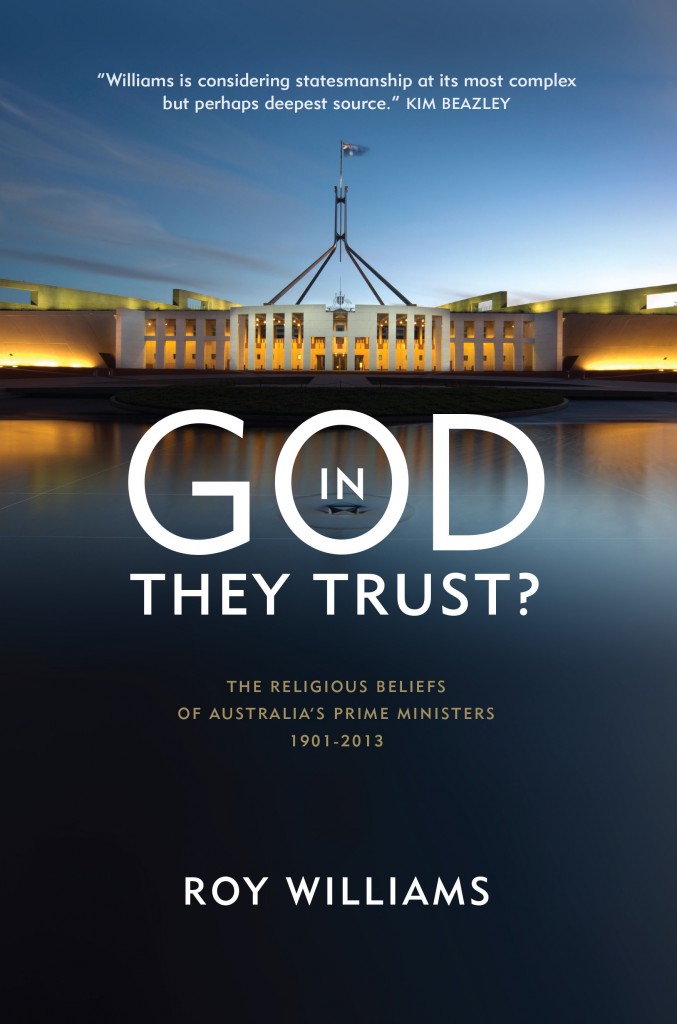

News of the death of former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser has sparked many a reflection on his influence and legacy. Author and commentator Roy Williams penned a chapter on Fraser for his book, In God They Trust: The Religious Beliefs of Australia’s Prime Ministers, published by Bible Society Australia. Here, we extract a section of that chapter. To purchase the book, click here.

Sir Garfield Barwick once sneered (ungrammatically): “Fraser, like wealthy sons very often are, feel they’ve got to be doing something for the deprived.” [2] To be so accused should be a badge of honour. Fraser built the best record on human rights of any prime minister in Australian history – his response to the “problem” of Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s was a model of principled, constructive charity, a million miles from Tampa, the Pacific Solution, children overboard, “Stop the boats!”, the Malaysia Solution, the “no-advantage” test and other cruel expediencies since 2001. Fraser behaved like the Good Samaritan. Instead of asking “How can we avoid these people?” he asked “How can we help them?”

Sir Garfield Barwick once sneered (ungrammatically): “Fraser, like wealthy sons very often are, feel they’ve got to be doing something for the deprived.” [2] To be so accused should be a badge of honour. Fraser built the best record on human rights of any prime minister in Australian history – his response to the “problem” of Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s was a model of principled, constructive charity, a million miles from Tampa, the Pacific Solution, children overboard, “Stop the boats!”, the Malaysia Solution, the “no-advantage” test and other cruel expediencies since 2001. Fraser behaved like the Good Samaritan. Instead of asking “How can we avoid these people?” he asked “How can we help them?”

But it is not clear that Fraser is a Christian. His religious beliefs are hard to pinpoint: over the course of a long life he has said different things. While usually categorised as a Presbyterian [3], he was married in an Anglican church.* The charity and international aid organisation with which he became associated in 1987, CARE Australia, has no religious affiliations.

Fraser’s religious background was an unusual hybrid. His father Neville was from a long line of Scotch Presbyterians, but his mother Una had both Anglican and Jewish antecedents. She identified as Anglican until her marriage, but then adopted her husband’s denomination. [4]

Theirs was a fairly dour strain of Presbyterianism: “disciplined, stern and elitist … with the emphasis on man’s sinfulness”. [5] It was also stridently anti-Catholic, a fact Malcolm Fraser has always lamented. As a boy, he frequently overheard conversations about Catholics – “how they were not to be trusted”. In his memoirs he recalled asking his father: “What’s the problem? What’s the matter with Catholics?” The reply was curt: “Well, they are different; they owe their loyalty to the Pope.” Fraser speculated that “if my sister [Lorri] had wanted to marry a Catholic, my father would have just cut the traces. He really would have. He felt very strongly. On other things he was very reasonable, but this was a common prejudice at the time.” [6]

A more attractive feature of the Frasers’ faith was the emphasis on charity – of a noblesse oblige sort. During the Depression Fraser’s paternal grandmother, Lady (Bertha) Fraser, would be driven around Melbourne by her chauffeur, distributing food to the unemployed. [7]

Fraser attended three schools – all private, exclusive and (interestingly) Anglican rather than Presbyterian. The first, in 1938-39, was Miss McComas’s school in Toorak. (Then the preparatory school for Geelong Grammar, it is now known as Glamorgan. [8]) Then, primarily for health reasons, Fraser’s parents decided he should board at Tudor House, a preparatory school in Moss Vale in the southern highlands of NSW. He was there for four years (1940-43).

One of the stated priorities of Tudor House was the “spiritual growth” of its pupils. On the evidence of Fraser’s letters back home this was not one of his own priorities. [9] Even so, Christianity was always in the background. In 1943 Fraser was in Common Room, and occasionally it was his duty to read the lesson at the daily chapel service or to say grace at meals. [10]

His next school (1944-48) was Melbourne Grammar. The headmaster during Fraser’s time, J.R. (Joe) Sutcliffe, described his overriding aim as follows:

I want it to be a recognised fact that, to say that a man has been educated at Melbourne Grammar School is the same thing as to say that he is a Christian gentleman. [11]

Malcolm Fraser won a Scripture prize in 1946. [12] But the school did not inspire him to a phase of religiosity, and overall he retained no great love for it. [13] Philip Ayres’ conclusion in 1987 was that Fraser’s time at Melbourne Grammar “seems to have contributed nothing in particular towards [his] qualities and resources”. [14]

In summary, by the time Fraser left school his religious beliefs were undeveloped. He knew the rudiments of Christianity but little more. His mother’s Jewish ancestry had been concealed from him. At Melbourne Grammar, he recalled in his memoirs, he “needed to have it explained to him what a Jew was, and why the Jewish students did not go to chapel”. [15]

In 1949 Fraser was sent to Oxford University to study politics, philosophy and economics (a course known as Modern Greats). By his own admission he came ill-prepared [16], and, to try to catch up, he read widely and voraciously. While never distinguishing himself as a student, by the end of his time at Oxford he had digested the works of, among others, Machiavelli, John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Descartes, Rousseau, Bertrand Russell, Arnold Toynbee, A.J.P. Taylor and John Maynard Keynes.

Fraser’s period at Oxford pushed him toward unbelief. At Magdelen College he was influenced by his tutor, Thomas Dewar (Harry) Weldon, a winner of the Military Cross in World War One and a notable man at Oxford. Fraser admired him. [17] But Weldon did not get on with several more traditionalist Oxford dons, including the legendary Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. Lewis regarded Weldon as “the most hard-boiled atheist he had ever known”. [18]

_________________________________________________________________________________

For the full references, please see ‘In God They Trust: The Religious Beliefs of Australia’s Prime Ministers. Purchase it here.

* Tamie Fraser (nee Beggs) is an Anglican. She married Malcolm in 1956 in the small Victorian town of Willaura, near her family home, at the Anglican Church of All Saints. The Rev. Phillip Burgess performed the ceremony. In 2007 Tamie was asked by Susan Mitchell whether she believed in God. She replied: “I do. A very strong belief ever since I was a child. But it’s a relationship between God and me. It doesn’t have a lot to do with the institution of the church. I am C of E, which stands for Christmas and Easter.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?