Australia made a unique contribution to international religious printing with the first Christian Scriptures printed here, which were in Tahitian and Maori languages.

“Set aside for a moment the potential cost of colonisation to indigenous peoples and cultures, the effect of this example was to publicise Australian religion in its printed public sphere, as well as in Europe, that Australia’s first internationally known religious printed publication was in Tahitian and later Maori languages. This is Australia’s unique contribution to international religious print,” said Dr Timothy Stanley during a talk on Printing Religion in Australia at the State Library of NSW in Sydney earlier this month.

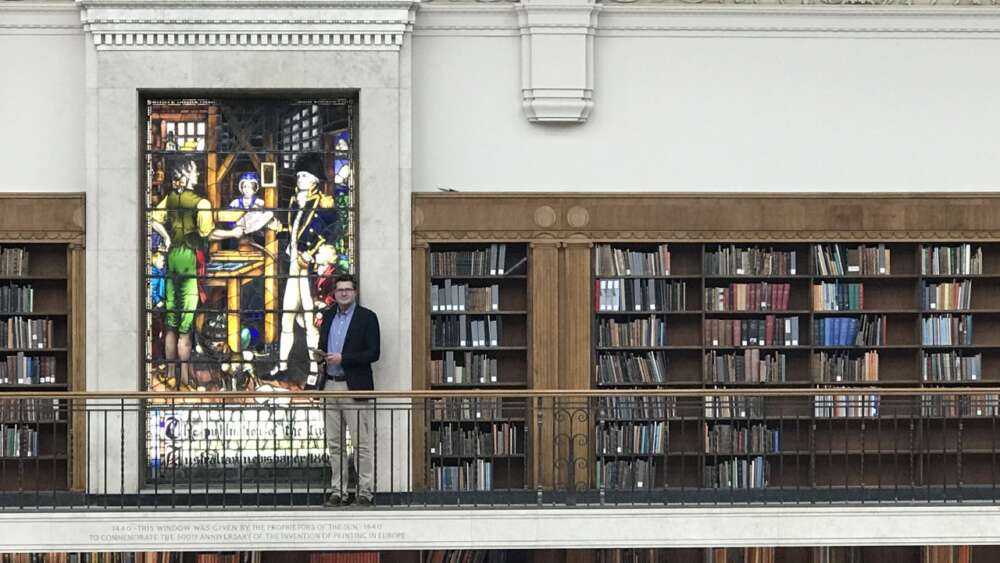

Stanley, who is a senior lecturer at University of Newcastle, as well as the State Library’s Australian Religious History Fellow for 2018-19, was giving a paper on how print was employed to maximum effect in Christian cultures of the Enlightenment era.

In hunting for early Bibles in Australia, he said he had not been able to find any whole printed Bible before the 19th century.

The earliest printed edition of the Bible comprised extracts of the New Testament in the Tahitian language – printed by Howe’s government printer in Sydney in 1814.

“It was evidently erroneously described in its sale in London as the first book printed in Australia,” Stanley said.

“However, it is the first book of Christian Scriptures printed in Australia, if you think of it just in terms of the New Testament, which is notable. It’s notable when one considers the importance of print in expressing religion in public. This particular text, however erroneously attributed, was widely publicised in London as well as Australia in the Sydney Gazette, December 3rd, 1814.”

Stanley said the other early translation was of the Maori language, which was printed in Sydney in 1827.

“It reflects their particular interests in congregational hymns, as well as an extension of missionary interest towards indigenous cultures.” – Timothy Stanley

“It includes the first three chapters of Genesis, the first chapter of the Gospel of John, 17 verses of Exodus and 30 verses of the Gospel of Matthew, the Lord’s Prayer and then some hymns,” he said.

“Four hundred copies of this text were printed as the first translation into the Maori language at a cost of 41 pounds, which sounds like a good deal.”

He noted that this translation was more widely known because funding was provided by the NSW Auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society, the precursor to Bible Society Australia, publisher of Eternity.

“In each of these cases of Australia’s early printed Scriptures, it’s notable that they were fragments – it’s a kind of editing of the texts that Australian print produced. It reflects their particular interests in congregational hymns, as well as an extension of missionary interest towards indigenous cultures,” he said.

“It provides a kind of portal and a kind of lost insight into that Awabakal language and culture.” – Timothy Stanley

He pointed out that the interests of the Bible Society and missionaries resulted in the printing of primers and dictionaries as well as Bible translations.

“These languages preserve key insights into the cultures of these various peoples. This is particularly true of the case of Lancelot Threlkeld’s translation of the Gospel of Luke into the Hunter River Valley language. This was published well after Threlkeld’s missionary activity ended in 1891, but his dictionaries were published much sooner. And today, scholars have argued that, while its missionary impact was marginal, it provides a kind of portal and a kind of lost insight into that Awabikal language and culture. And it now features in the best contemporary scholarship as a kind of window into the past.”

He noted that in Newcastle, the university’s welcome to country always is to the Awabakal people.

Asked by Eternity if he had seen any copies of a Bible made for bush life, Stanley said he hadn’t, although he knew books were made for the Outback.

“I found diaries – there was a Presbyterian minister in Queensland who brought all of his books and the cockroaches are after his glue, and he’s been told that he has to lacquer them to protect them,” he says.

“I’d actually asked to go wander around the stacks [of the State Library] if they’ll let me because I’m just looking for lacquer!”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?