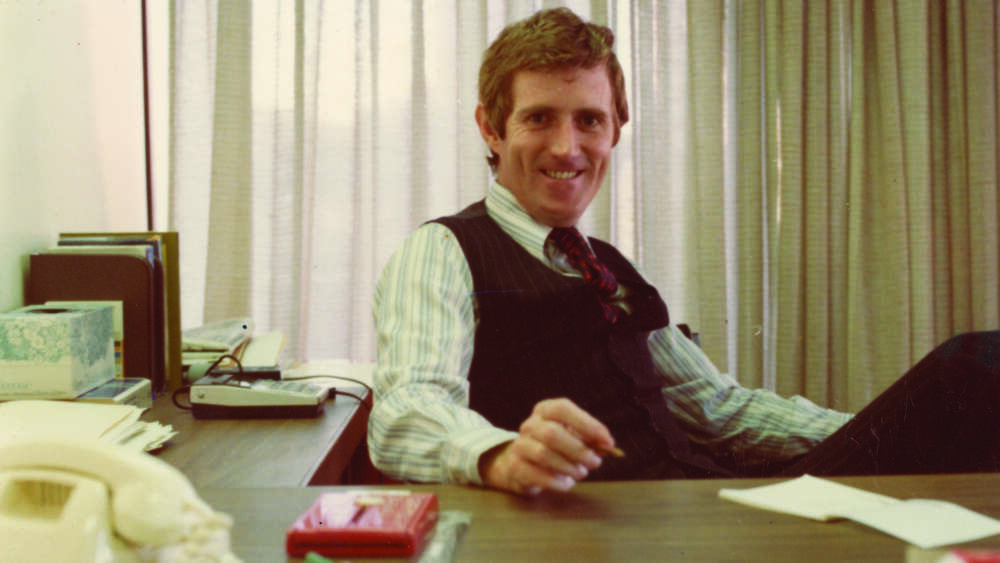

It was while Sydney ad man Tom Glynn was at the top of his game, working for the prestigious agency J Walter Thompson, that he decided he wanted to move from selling products to selling a person, Jesus Christ.

The high school drop-out and son of an SP (illegal) bookmaker had begun his advertising career as a messenger boy at age 15 – six years before becoming a Christian.

He thrived on the challenging competitive atmosphere and advanced up the ladder to work as account manager for top agencies in Singapore and London before returning to Sydney.

In his heyday, Glynn worked with scores of blue-chip companies and several brilliant Australians who went on to become famous, including social critic Donald Horne, restaurant critic and arts supremo Leo Schofield, social researcher Hugh Mackay, publisher Richard Walsh, novelist Bryce Courtney and artist Ken Done.

In fact, it was Mackay, by changing his whole understanding of how advertising works, who sparked Glynn’s career move into “selling Jesus”.

“I had been raised to regard advertising in military terms – we used words like strategy, objectives, execution, targets, etc,” Glynn writes in his autobiography, God’s Ad-Man.

“That seemingly aggressive approach was described by Hugh as the ‘injection’ model of communication, where you think of your message as being rather than a potent drug and the medium as being the syringe you use to inject your message into the brain of your unsuspecting audience.”

“It’s not what the message does to the audience but what the audience does with the message.” – Hugh Mackay

The only problem with the injection theory is that it doesn’t work, he was told, and people do not change their minds in response to every persuasive message that reaches their brains.

The power of advertising, according to Mackay, lay with the audience, not the message. “It’s not what the message does to the audience but what the audience does with the message, which determines the outcome of communication,” Mackay said, in a memorable dictum that Glynn found “mind-blowing”.

It meant that effective communication started with getting inside the heads of the audience, to discover their attitudes and predispositions because people see the world through the filter of their beliefs and seek reinforcement of those beliefs.

“At that time [the 1970s] – and perhaps even today – the ‘injection model’ of communication was alive and well in the Church,” Glynn writes.

“I remember a well-meaning, dedicated Deacon saying all we had to do was to get people to read tracts and they would become Christians. If only it were so easy!”

“The Church must get inside the community’s point of view and work from that, as if it were the Church’s own,” he writes.

“For example, the Church needs to understand the ‘experience generation’ (where ‘being, doing, feeling and experiencing’ outweigh ‘saying’ and ‘authority’).”

Mackay’s insistence that the most effective communication channel by far was personal relationships contained an important message for the Church, he believed.

“Many churches and groups think that they’ve got to get out there and have the big publicity campaign but the best way is person to person. But sadly, we’re not equipped to do that effectively, so that’s a challenge,” he tells Eternity in an interview.

“Advertising is mainly there for confirmation that you bought the right product or service. it’s not very effective in converting people to your way of thinking.”

Like most children of the 1940s and 50s, Glynn attended Sunday school, Christian Endeavour and the Boys Brigade in the inner west of Sydney, but did not commit his life to Christ until the age of 21.

It happened on a camping trip when he took with him three books: the Bible; Basic Christianity by John Stott; and a book of sermons by an American liberal Baptist preacher, highly influential in his day, Harry Emerson Fosdick.

Glynn writes: “I had time to reflect, whereupon I finally accepted Jesus, not because of my sins and as a pathway to heaven, but because of His life, ministry, death and resurrection, and as the One to follow. I was also impressed by Jesus’ disciples, who had witnessed his resurrection and who went on to claim that He was the Son of God. They kept the faith when facing death. I was also impressed by St Paul with his dramatic and life-changing conversion on the road to Damascus, and with his letters to small struggling churches in Asia Minor. ”

“I finally accepted Jesus, not because of my sins and as a pathway to heaven, but because of His life, ministry, death and resurrection, and as the One to follow.” – Tom Glynn

Glynn returned from the camping trip a changed person. After apologising to his mother for myriad domestic differences, and getting baptised, he “threw [him]self into a new mission – to bring the insights of advertising/marketing into the Church”.

So at the age of 32 with 16 years of experience in the advertising game behind him, Glynn courageously opened his own advertising agency – with a burning desire to help Christian ministries and charities survive a period of high interest rates and depressed donations using the principles and techniques of modern advertising.

With the opening of Tom Glynn Advertising (TGA) in 1974, he blazed a trail in a new business model that provided consultancy advertising services for a monthly fee.

“At that time, the idea of an outside organisation handling the client advertising marketing fundraising was quite unique. Before, they would use us for a one-off job, where we designed a better leaflet for them or did an annual report and then you wouldn’t see them for another year,” he tells Eternity.

“What I created was a model that many corporations were then using, which was a consultancy, but mine was on a basis of a paid monthly fee and that was an innovation.”

One of his most treasured “raindrops from heaven” was the Christian bank manager who took a chance and lent him enough money to start the agency even though he had only two clients, the Anglican Home Mission Society (now Anglicare) and Scripture Union.

Despite becoming known as a Christian agency, TGA thrived and in 1975, Glynn orchestrated a wildly successful but somewhat controversial television campaign for the US giant Thomas Organs (whose Australian distributor was Open-Air Ministries). It featured the flamboyant American pianist Liberace, with filming taking place in his Las Vegas garage, complete with chandeliers.

Despite blowback from one client, the Australian Council of Churches, the Liberace campaign put TGA on the map and paved the way for 14 successful years servicing a “who’s who” of Australian Christian bodies while topping up the coffers with regular commercial clients. He sold TGA in 1989, but stayed in the industry in various capacities for another two decades.

Glynn tells Eternity that when he sat down to write his autobiography, he had three aims in view. The first was to encourage Christian organisations to be more professional in their communications.

Secondly, he wanted to describe his battle with depression, which went untreated for a long time while he was at the peak of his career.

And finally, he wanted to write about his experiences of surviving in an industry that was not sympathetic towards the Christian message.

“I was looking for exterior escapes – going on holidays, going to the healing service in Sydney at the cathedral, doing growth movement, praying.” – Tom Glynn

In his candid descriptions of his struggle with depression, Glynn writes that he kept it secret for more than 20 years, hiding behind his extrovert “bushy-tailed” mask and feeling too embarrassed to talk about it.

It was allied with his struggle with coping with rejection – ironic since he was in a business where rejection was inevitable and frequent.

He searched for theological answers, but continued to struggle with what he thought was a mid-life crisis that made him dread going to the office on Monday mornings.

“I was looking for exterior escapes – going on holidays, going to the healing service in Sydney at the cathedral, doing growth courses, praying,” he tells Eternity.

“Too many Christians felt that all we had to do was pray and read the Bible and trust God and you will heal. But when you’ve got this serotonin in the brain not functioning very well, it doesn’t matter.”

After hitting a crisis where he felt suicidal over the Australia Day long weekend in 1985, Glynn found the right psychiatrist, who diagnosed him as suffering from a genetic illness and prescribed anti-depressant medication, which relieved the symptoms.

Glynn comments: “As CS Lewis said, it’s God’s foghorn to us when we suffer. And when we do suffer, it’s an awful time, but if you come through it, you look back and you say, ‘well, I’ll give thanks to God. That was helpful for me in my understanding of spirituality and growth.’ So yes, awful time, dreadful time. Unless you’ve been depressed clinically, you have no idea.”