King James or Good News – do we need to choose?

A letter from a Bible Translation Consultant

Bible Society Australia, which owns Eternity, recently received a question about the accuracy of different translations of the Bible from one of its supporters, Brian. Brian asked specifically about the Good News Bible in comparison to the King James Version (KJV), quoting from different parts of the Scriptures.

As you may know, Bible Society is actively engaged in Bible translation work, both in Australia and internationally. Here, Bible Society, working collaboratively with other Bible translators and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander translators, is slowly reviving languages that had gone to sleep, as well as revising different Indigenous Bibles in need of a more contemporary presentation.

So, when Brian asked his question, the obvious person to go to was one of the members of the RIMS (Remote and Indigenous Ministry Support) team, Sam Freney. Dr Freney is one of our Bible Translation Consultants, who positively loves his job, so he couldn’t help but provide a fulsome answer. It was so helpful we just had to share it with you, our Eternity readers. Here it is, a letter to Brian and to you …

Dear Brian,

Thanks for some really good questions. I’m glad that you’re paying close attention and asking good questions about the text – it’s an excellent habit.

Like all good questions, your questions have answers that are not entirely simple or straightforward. They do have answers though, so I’ll try to pay attention to not only the particulars of the verses you’re talking about but the broader pattern of translation.

Could it be a frog or a cat?

I don’t know if you’ve ever learned another language. If so, I’m sure you’ve come across times where translation from one language to another forces you to make a choice over what to communicate.

Sam, the translator and author of this letter!

Here’s an example I remember from hearing from Don Carson, a biblical scholar. The French phrase “avoir un chat….” could be translated very literally as “to have a cat in the throat”. But French people use this to talk about having a hoarse throat – our equivalent phrase is “I have a frog in my throat.” When you translate this phrase, you have to decide whether you’re going to reflect the words used (in which case you’d have to include ‘cat’ in your translation) or reflect the intended meaning (in which case you’d include ‘frog’).

Different Bible translations end up sounding different because they have slightly different overall aims: some want to give you a better feel for the original words and sentence structure in the original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek), while others intend for you to understand the meaning conveyed by the original above all else. Speaking generally, the Good News Bible is more in the second camp than the KJV is.

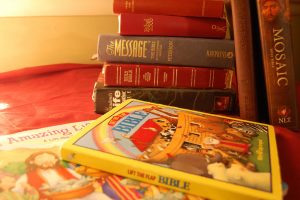

The value of many English translations

There are also other intentions of a translation that come into the differences, such as the intended audience, general literacy level and reading ability, and other considerations. Bibles often have a preface of some kind that will outline the purposes the translators hope their translation will accomplish. Neither style is necessarily better than the other, they just have different aims. We’re blessed to have multiple different English translations, and we can read them all if we want to!

With that in mind, let’s look at some of your questions with the two texts you’ve got before you, the Good News and the KJV.

The NIV version

Psalm 23 reads “The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want” in the KJV, and “The Lord is my shepherd, I have everything I need” in the Good News. Here you can see this different translation philosophy expressed. The KJV is an older style of English, for one – it was first translated back in 1604 after all! But it puts the verb at the very end of the sentence, which is a bit uncommon in English (I shall not want), possibly reflecting the Hebrew sentence structure where the verb is at the end of the sentence. But of course, it can’t do that perfectly, since a word-for-word Hebrew to English translation would be nonsensical. It’s only four words long, and is something like, “God shepherd-of-me, not I-want”.

Poetry or plain English? You decide

The Good News communicates the same idea here. What does “I shall not want” mean, but using other words? It means that God is the provider, who cares for those he looks after and provides everything for us so that we do not need or lack anything. So, it says that in much plainer English: “I have everything I need.” Arguably less poetic, but also a bit clearer for an average reader. If you compare the rest of this Psalm between the KJV and Good News, I’m sure you’ll find other examples that parallel this one: the Good News generally opts for a plainer style that aims to communicate the meaning as the most important thing; the KJV has additional aims of poetry, artistry and original language style.

Neither is necessarily better than the other. But it does explain why they’re different.

Your Isaiah 3:12 example is a little more complicated. The second half of the verse has the same pattern as Psalm 23, in that the Good News has a meaning-focussed translation. “You don’t know which way to turn” means the same thing as “destroy the ways of thy paths”, but it’s a bit clearer if you don’t fully appreciate that poetic language.

Making choices in language translation

But the first part of the verse is where I suspect your question is. And this is where it’s clear, once again, that we’re translating from one language to another. And sometimes, language isn’t as clear as we like. There’s not a mathematical precision. Take the English word ‘rogue’, for example. Is a ‘rogue’ a loveable swashbuckling ruffian or a vicious cut-throat? It could be either, depending on context. Or ‘bow’: bending at the waist, a tool for shooting arrows, the front of a boat or the shape you can tie with a ribbon? Usually, context tells you, but not always. For example, “Aaron walked up to the archery range and took a bow.”

This happens to be an example like this. The Hebrew words in the original text of this verse can be read in a couple of different ways, and that’s why we end up with the moneylender or youths differences. This seems like a good deal of ambiguity, but in fact if we once more look at the two verses and apply the same principles as above, we do come out with the same overall meaning, just expressed in different language: God’s people are being oppressed and down-trodden by unexpected groups of people, so that they are at a loss for what to do with themselves.

The value of different translations

Tying it all back in again: there are many many different English translations of God’s word. That’s a real, genuine blessing for all of us – we don’t all need to learn Hebrew,

Which Bible is the best translation? Cathy Stanley-Erickson1 License

Aramaic and Greek to access God’s word. They’re different, but that’s also good because we can read them all if we like and get different benefits from each one. The more you read different translations, the more you appreciate the kind of choices the translators have made.

The Good News and the King James Version are truly, fully, God’s word.

Every major English version has been translated by a team of people who collectively have more letters after their name than are in most Bible verses. They’re experts in their fields and use the best original manuscripts available. No major English version is a translation of a translation of a translation, but they’re done from the original languages by skilled and thoughtful Christian scholars.

So, the short answer to your question, after a very very long answer above, is this: you need have no concern that you have not been reading the true scriptures. The Good News and the King James Version are truly, fully God’s word.

Sam

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?