The Indigenous Bible translation glass is half-full, not half-empty

When I think about the task of Bible translation, as a white person, as a European, I often think about the enormity of the task. I consider that there are some 7000 languages in the world. Then I consider that the whole Bible has been translated into 717 languages, the New Testament into another 1582 languages and portions of the Bible into a further 1196 languages.

These numbers are baffling. If I take a glass-half-empty approach, I could become dismayed that only 47 per cent of the world’s languages have some access to the Bible.

Turning my eyes to Australian Indigenous languages is equally baffling. Census data from 2016 reveals there are speakers of 171 Indigenous languages in Australia. Among these, only Kriol has a full Bible. There are a further 15 that have the complete New Testament, and 36 more languages have some books or verses from the Bible.

Maybe there’s no glass; maybe it comes from a stream, the rain, and maybe I should forget about the glass.

Many positive Bible translation projects are happening in Central and Top End Australia. Some translation work or Scripture engagement materials are being produced in at least 25 Indigenous languages around Australia. There is always more that can be done, but God’s word is impacting lives and communities.

With only 30 per cent of Australian Indigenous languages having some portion of Scripture, it would be easy to become overwhelmed. But after talking to Bible translator Djawut, I’ve realised that the glass is maybe even better than a glass half full. Maybe there’s no glass; maybe it comes from a stream, the rain, and maybe I should forget about the glass.

Last year, as Bible Society’s Indigenous Engagement and Promotions representative n Darwin, I interviewed Djawut and five other Indigenous Christian leaders involved in Bible translation. They represent four languages: Rembarrnga, Dhuwa Dhangumi, Gurindji and Warlpiri. Two of these translators previously worked on the Kriol Bible and another on the Djambarrpuyngu Bible. Here are a few highlights from my interviewees with these translators.

Gurindji language, Top End, Northern Territory. Translator: Lorna. Interviewed May 26, 2021 in Darwin.

The Gurindji language is spoken by a few hundred people in the Kalkarindji region of the Northern Territory, north of the Tanami Desert. There are a further thousand or more people who speak a developing “Gurindji Kriol” which is a mixture of the traditional Gurindji language and the Kriol language. It might be possible to argue that it would be most effective to translate into Gurindji Kriol, but as that is a spoken language only, people prefer that Bible translation be done into the traditional Gurindji language. Only one book of the Bible, Ruth, has been translated, back in 1984. In many ways, any project in Gurindji is like translating for the first time.

Lorna Ryan

God put it on Lorna’s heart to translate Luke 2:6-12 at a translation workshop held in Darwin in May 2021, for a project in which the Christmas story would be told in a book containing 40-plus Indigenous languages. (The book will be published soon.)

Lorna: This was my first time doing this translation. It has given me confidence, and I would like to continue. To share with other non-Indigenous, so they can understand us, so we can learn from each other. We can share so much from our language and culture. We are happy sharing it with you, so you can know more and share it with the younger generation. I believe that our understanding and knowledge is coming from our Saviour. We learn from you too, to write our languages and give us more courage and confidence to write.

Paul: How did you feel about the learning process of doing the written translation?

Lorna: Good. I enjoyed it. I learned more to write it. I can speak it, but the writing was difficult … we know how to speak it, but in the writing, “Oh, that’s how it’s spelled.”

Paul: Did you feel confident before the workshop?

Lorna: Yes, I felt confident. I was determined to get it done. It was such an opportunity, so I just kept pushing myself. The Holy Spirit guides us and teaches us. I never give up on praying. God gives us strength to carry on … I want to do more … I’m going to start on Luke when I go home.

Paul: Do you think the whole Bible should be translated into Gurindji language?

Lorna: Yes!

The Lord has given Lorna the courage to tackle a very difficult task. I was inspired by her faith as she declared that she wanted to see the whole Bible translated into Gurindji. I would rather encourage this faith than say it can’t be done. This was a real challenge to me. I set out to write an article explaining why Bible translation is so difficult and why it’s a slow process in Australia. But maybe our problem is that we don’t have enough faith, that we don’t believe it can be done. Perhaps the biggest issue is whether the Australian Church will pray and believe that the task can be done. Out of this prayer and belief, action, support and people should follow.

Dhuwa Dhangumi language, Eastern Arnhem Land. Translator: Djawut. Interviewed March, 2021 in Darwin.

Dhuwa Dhangumi is a language that represents four Yolngu clans: the Gälpu, Golumala, Ŋaymil, and Rirratjiŋu. The language is spoken in Eastern Arnhem Land. Djawut is the sole Bible translator. He is an experienced translator, having done a lot in the Djambarrpuyngu New Testament. Thanks to Djawut’s hard work and help from support workers, the Gospel of Mark was published in Dhuwa Dhangumi and dedicated in 2017. Following publication, support workers recorded Djawut reading the Gospel of Mark, so others could also listen to it as audio. The Gospel of Mark is the only Scripture currently available in Dhuwa Dhangumi.

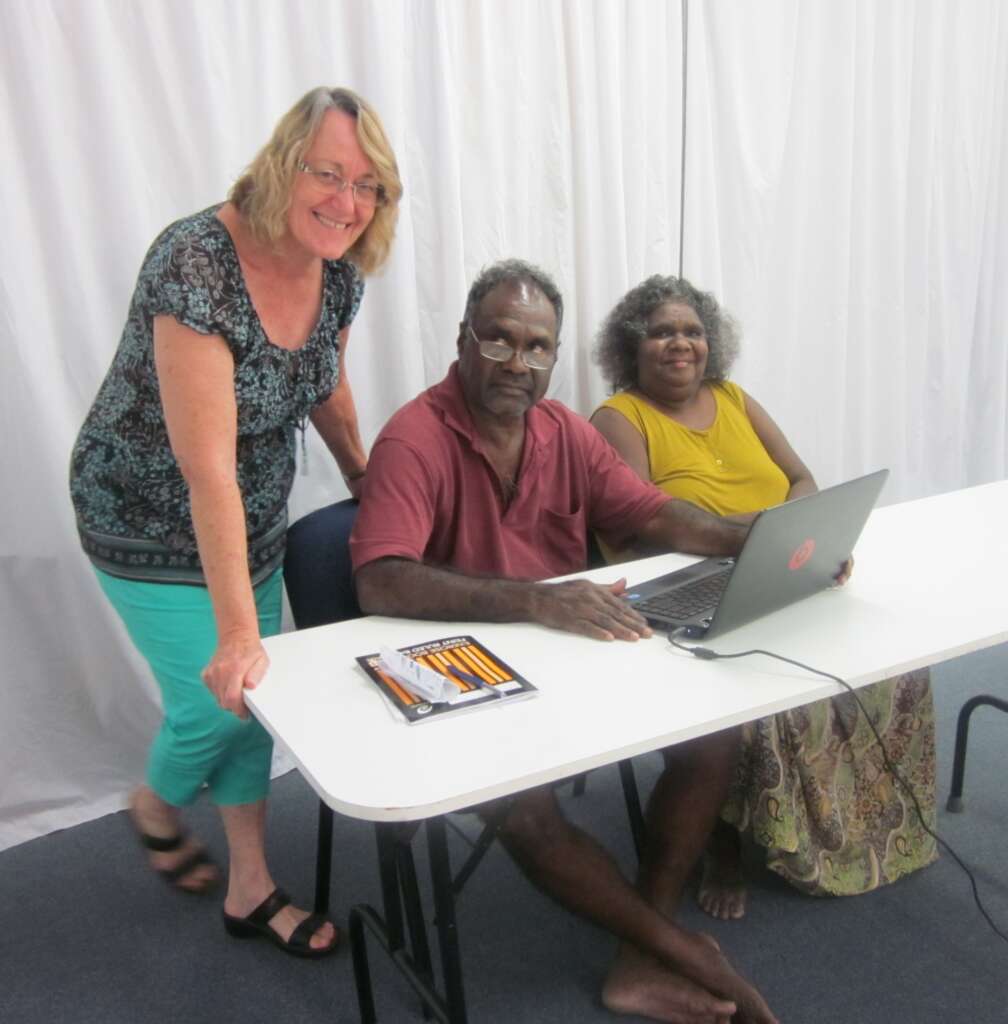

Djawut Gondarra, centre, with Mally Mclellan, left, and Yurranydjil Dhurrkay, right

Paul: How do you feel about doing Bible translation in Dhuwa Dhangumi?

Djawut: I feel comfortable. I feel just right. When I first started learning to become a translator, it was in Djambarrpuyngu. I grew up with Dhuwa Dhangumi language … Djambarrpuyŋu language helped me with the sounds … People from these clans support me. All the elders from these clans said, “Go ahead, do our Bible. You can do it.”

Paul: Is anybody else helping you?

Djawut: Not at the moment … I’m doing this because my people don’t understand English. I don’t know why God called me to do this.

Paul: Is it easy for people to read?

Djawut: For some educated mob, for others no.

Paul: Praise God that there’s some water in that cup, some translation of God’s word in Dhuwa Dhangumi. You can’t do it all as one person.

Djawut: Yes, you’re right – one person will not. But when I work, I don’t think that way, I just work. Because God knows. I tried my way, went down to Yirrkala to find someone. Maybe that’s not God’s way, maybe I’ll just work. When I did Mark, when that was finished, I went down to this consultant, and then everything went well, and we had a dedication ceremony at Yirrkala. I was blessed. This is what you, God, want me to do. And my aim is, I’m doing this for my people that don’t understand English so that they will listen and understand.

Djawut is realistic about the task of Bible translation. He is working on his own, persevering through the Gospel of John. He is under no illusion that he might even finish the New Testament, let alone the Old Testament. But all Bible translation he does, no matter the amount, is of immense value.

Rembarrnga language, Top End, Northern Territory. Translator: Miliwanga. Interviewed June 10, 2021 in Darwin.

Miliwanga is an energetic woman who is fun to talk to. She’s always in demand from various government agencies. Miliwanga and I were surveying the Rembarrnga language in August, and I had to cancel our plans one afternoon when she received a call asking her if she could meet with the Governor-General the next day. I was outranked!

Miliwanga also worked on the Kriol Bible translation for many years. During those years she would often tell her family that she wanted the Bible to be translated into Rembarrnga.

In May 2021, I had the great joy of working with Mili during a translation workshop to translate the verses Luke 2:6-12 for the Christmas project in many new languages mentioned earlier. I worked with her as she finished the translation, and when we read it together, it was like witnessing the birth of a new baby. We both had tears, as we knew this was an eternal moment.

Paul: Can you remember when you started to feel like you wanted to have the Bible in Rembarrnga?

Mili: Whenever we would sit as a family, we would talk about where the Bible came from. We would tell stories about where the Bible came from, and who the tribe was, their history and their ceremonies. For us, the Bible is okay; we can read the word, but we can never own it because it doesn’t belong to us. We will always have that in us. But God has given this specific word, the Bible, to the people who spoke that language, all those Israelite people, all the Jewish people, and so now with that translation, we have big respect for them, but we see it in our perspective, what God, what Messiah is talking about because we have all that already in our spiritual tradition. We have our moral values. We have wisdom and quotes. Like in Proverbs, the book of Solomon, Psalms. I was so amazed at Psalms because Psalms are a singing prayer, and I said, “Oh, we already have this, when we go out bush to pay respect to the ancestors and to the higher being, which is God or Wunngarr. It’s like singing praise, acknowledging and paying respect, saying thank you for everything. Or when we are going fishing, “Lord you bless us, whatever we catch today, we are grateful and thankful,” and we sing it, just like in the Psalms. It’s so wonderful.

Paul: How much of the Bible do you think is possible to translate into Rembarrnga?

Mili: First of all, that book of Genesis is very important. Most all those small New Testament books.

Paul: Do you think the whole Bible should be translated into Rembarrnga?

Mili: Of course!

Paul: How many people do we need?

Mili: We filled up the whole room for Kriol.

Paul: So how long would it talk to do the whole Bible?

Mili: Oh, a long time – I would probably be in my 80s.

Miliwanga is in her 60s now, yet she is prepared to give a lot of energy to Bible translation for the next 20-plus years of her life. This is still not a simple prospect. Organisations such as Bible Society and AuSIL can support Bible translation, yet people like Mili are in constant demand from their communities and government agencies. They want to serve their people as best they can. They would also like more time to give to this task of eternal importance. We pray for more workers, both for the support organisations and among Rembarrnga speakers. It will take a full team to make any significant headway.

When people hear the word of God in their heart language for the first time (no matter how well they speak it), the impact is more than a native English speaker can ever appreciate. People know for the first time, “God loves my people too.” Therefore any amount of Scripture translated into any Indigenous language can have untold and eternal blessings for people. We should never underestimate the impact that even one verse can have when someone hears it in their language for the first time.

While there are plenty of practical questions about the task of Bible translation in Indigenous languages in Australia, we can all take a leaf out of Djawut’s book. He has been called by God, he does the work, and he doesn’t worry about the future. The living water of God’s word can come to untranslated languages like Rembarrnga or Gurindji.

All interviewees have permitted their interviews to be used in this article.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?