What Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister really thought about the Bible

America’s first President of the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt, once quipped that “a thorough understanding of the Bible is better than a college education”.

In our own time, Queen Elizabeth II observed: “To what greater inspiration and counsel can we turn than to the imperishable truth to be found in this treasure house, the Bible?”

In his speech to the Bible Society in 1960, the Prime Minister extolled the spiritual riches of Christian Scripture

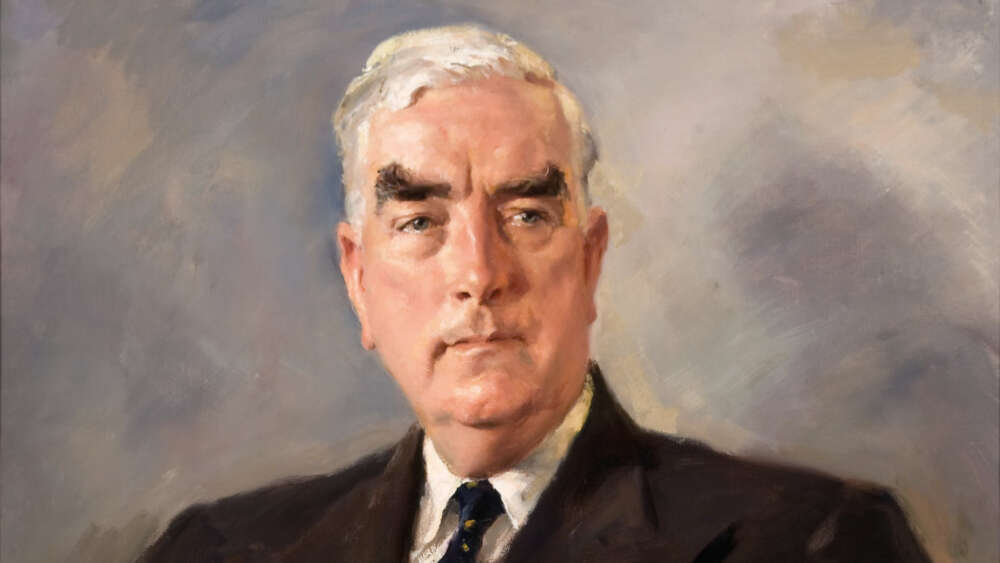

What then, did one of Australia’s great leaders have to say about the Christian scriptures? In a country whose public figures seldom wear their faith on their sleeves, it may come as some surprise that Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister, Robert Gordon Menzies (1894-1978), had much to say about the text that is the very basis of Christianity.

Born to a Scots Presbyterian family in regional Victoria, Menzies grew up reading the Bible together with The Pilgrim’s Progress and the Presbyterian Hymnal. In young adulthood, regular Bible reading was encouraged by both the Student Christian Union at Melbourne University, of which he served as President in 1916, and the conservative evangelical clergyman, C. H. Nash. As he entered political and public life, Menzies reading of the Bible remained a constant, even where his church-going ebbed and flowed.

Fond of employing Biblical turns-of-phrase such as “my brother’s keeper”, “house of many mansions” and “the truth shall set you free”, Scripture was rarely far from Menzies’ mind and his explicit thoughts on the Bible were matters of public record. On two occasions as sitting Prime Minister, he addressed the Bible Society. The first was in July 1940 as wartime Prime Minister, and the second in his lengthy post-war reign as Prime Minister in February 1960.

Praising the Bible as “this great and immortal book”, the Prime Minister honoured it as both a literary masterpiece and a sacred text of faith. For Menzies, the traditional King James Bible represented the jewel in the crown of English literature and was “the great repository of our tongue.”

For this son of a lay preacher, however, the Bible was so much more than a brilliant piece of literature but the great wellspring of truth, wisdom and faith. In his speech to the Bible Society in 1960, the Prime Minister extolled the spiritual riches of Christian Scripture: “… in the greatest place, the Bible is the repository of our faith and inspiration. Never out of date, always up-to-date, always difficult of application and therefore stimulating to thoughtful people. It is the great source of faith, and of course that is why we ought to read it … Let’s seek the fountainheads – it’s all there! The story is there, the great history is there, the great gospel is there, the whole spirit of Christianity is there.”

In the Old Testament books of law, history, prophecy and wisdom, together with the Gospels, acts of the apostles and apostolic letters of the New Testament, Menzies saw the master narrative of God’s redemption of the world, the gospel of Jesus Christ and the birth of Christianity. These represented the “fountainheads” of Christian belief and the Bible contained them in their entirety.

Menzies chose the word “fountainheads” to remind his audience that for all the differences in doctrine and worship between the many churches, the Bible remained the focal point for Christian unity in an age where sectarianism still festered. As such, it was “better … to go to it than to be taken up too much with theological refinements”.

With Menzies regarding the Bible as the primary repository of Christian belief, he also viewed it as the supreme authority. To illustrate, the former barrister likened the primacy of the Bible to the Australian Constitution. Rather like a good lawyer deferring to the Constitution as the overriding authority in all matters of law, the Christian would return to the Bible as the ultimate source of authority in all areas of faith and practice.

His pronouncements on the Bible were more than merely the whispers of a cultural Protestantism or the Christian trappings to a civic religion.

Far from viewing it as a “dead letter”, Menzies also appreciated the Bible as critical to the vitality and growth of the church. After hearing a somewhat lifeless sermon at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, he suggested in his diary that the best way to fill the churches would “be to arrange that the Bible should always be read with intelligence and power”.

To be sure, Menzies’ reading of Scripture, though orthodox, was broad and not literal perhaps to the degree of some more conservative Protestant traditions. Like the Reverend Gordon Powell, the leading Sydney Presbyterian Minister of the 1950s and 60s, he took the Bible seriously but not literally. In Menzies’ eyes, the Christian faith was concerned more with the spirit of the Word than with the letter of the Word.

When Menzies spoke on the importance of the Bible in 1960, he was Prime Minister of a country where some 88.3 per cent of the population identified as Christian, compared with just 52.1 per cent in the 2016 census. As such, he was speaking into a decidedly more Christianised Australian culture than that of today.

That said, his pronouncements on the Bible were more than merely the whispers of a cultural Protestantism or the Christian trappings to a civic religion. In a world he saw as beset by the dangers of either a godless communism or a soulless materialism, the Bible could build character and give breath to the spirit of freedom in a democracy such as Australia.

In our own day, Menzies’ words remind us that this “always up-to-date” message can similarly quench thirsting souls with faith, hope and love.

David Furse-Roberts is a Research Fellow at the Menzies Research Centre and the author of the forthcoming book, God and Menzies: The Faith that Shaped Australia’s Leading Statesman.

Email This Story

This is a story worth re-telling, please share it