In the first of two blogs, Lewis Jones looks at how COVID has distorted our sense of time and space – but he offers a path to recovery.

At 7:07pm on June 26, 2021, in New South Wales, it seemed like a good thing that you had booked a rental cabin where you were going to stay with in-laws and some family friends for the school holidays.

At 7:08pm, it not only became illegal, but antisocial and a sign of your disregard for the common good.

At 7:07pm, you may well have been thinking nothing of drinking a beer at the pub while standing upright. At 7:08pm, it was illegal.

At 7:07pm, you were enjoying Opera in the Domain [in Sydney], mask free.

At 7:08pm, it became essential to know whether Opera in the Domain was a controlled outdoor public gathering because, if it was, you were now in contravention of an enforceable public health order.

This pandemic has changed our sense of who and what’s important – what we need to know, and who we need to obey, in order to get on with our ordinary life. Suddenly, we are at the mercy of 19 categories of public health orders, one category of which contains 82 individual orders.

As a result of daily briefings, we find ourselves knowing the name of the Chief Medical Officer (I guess a pandemic is a little like the Olympics for knowing the names of our swimming team). We speak with each other casually about case mortality, testing numbers, DNA fragments, R factors, and venues of concern (of which there were, at the time of writing, 259 in NSW).

The number of new things we are supposed to be on top of, but that are also changing day-to-day, has sky-rocketed since March 2020. The number of decisions we have to make every day now compared to February 2020 is enormous. We now need to decide every day whether to go to our usual workplace. Every time we think about going outside we have to decide if we’re allowed. We decide whether to take a mask with us when we leave the house and, then, when to put it on while we’re out.

We have to decide whether we can visit friends or go out to eat or, even, go out to eat with friends. When we visit friends, do the children count in the permitted number of visitors or not? Today, they do. Last month, they didn’t. The new FOMO in NSW is the daily briefing with Gladys and Kerry. What are the case numbers and venues of concern? Any new restrictions? Any unlinked community transmission?

All of this is stressful. It weighs on our minds and wears us down.

Scripture gives us two broad categories that can help us understand our present anxieties: one for the believer and one for the unbeliever.

This anecdotal picture of our newfound daily anxieties is borne out by research on both adults and adolescents. One quarter (25 per cent) of Australian adults exhibited mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety during the first month of COVID restrictions (March-April), which is five times pre-COVID levels. Also, adults were more than three times more likely to show clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety if they reported a high impact of COVID restrictions on their lives, compared with those who reported a low impact.

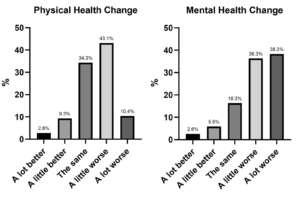

For Australian adolescents, rates of psychological distress at levels indicating probable mental illness have doubled relative to pre-pandemic levels. Nearly 75 per cent self-reported worse mental health and 40 per cent scored, in validated tests, over the clinical cut-off for severe health anxiety (Both figures below are from Li, et al).

While, encouragingly, almost one in five adolescents reported a positive impact on family relationships, over two thirds reported a negative impact on family stress.

One way Australians are responding to the increased anxiety is with alcohol. About 70 per cent of us are drinking more alcohol than usual, even while one third of those reported being concerned about either their own drinking or that of someone in their household.

Coping with anxiety and stress was the explicit reason given for the increase in drinking for 28 per cent of those surveyed.

The current struggles are real and it is unhelpful to trivialise them. But we can work on responding in ways that help us and help our neighbour rather than add to the problem.

Scripture gives us two broad categories that can help us understand our present anxieties: one for the believer and one for the unbeliever. Hebrews 12 tells us that, for believers, trials are the discipline of a loving father who is concerned for our transformation into the likeness of Christ and the harvest of righteousness reaped through that transformation. For unbelievers, Luke 13 reminds us that struggles are an indication that we are all deserving of the wrath of God and judgement is coming. This is a message our world needs to hear.

In thinking about how to manage our anxieties, Philippians 4:6 famously tells us “Do not be anxious about anything”. While such a blanket injunction has the potential to increase rather than decrease our anxiety as we are confronted with a genuine struggle to obey the Bible at this point, let’s pause and put that verse in the wider context of Philippians 3:20-4:7.

But our citizenship is in heaven. And we eagerly await a Saviour from there, the Lord Jesus Christ, who, by the power that enables him to bring everything under his control, will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body.

Therefore, my brothers, you whom I love and long for, my joy and crown, that is how you should stand firm in the Lord, dear friends! … Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice! Let your gentleness be evident to all. The Lord is near. Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.

If we trust in Jesus, our citizenship is in heaven and our king has everything under his control (3:20-21). So we are not at the mercy of the latest public health order, but rather at the mercy of the king who has already demonstrated his love for us by dying in our place. We can be confident that he has our best interests at heart and, in a time of acute health anxiety, we are reminded that these bodies of ours were only ever temporary and not predictive of the glorious bodies we will have in the new creation (3:21).

We must not trivialise our own struggles or the struggles of others but, remembering that we serve the king who is in control of everything and whose love for us in Christ cannot be questioned or taken away from us, our struggles are relativised. Our citizenship now and our future inheritance are both unshakably secure in Him.

In light of our security in Christ, we can afford to acknowledge our anxiety about all manner of things that are genuinely uncertain in the present. At the same time, we rejoice in our king and commit our anxieties to God in prayer, trusting that the one who loved us even to death cares about us and our worries and has a plan to turn them into a harvest of righteousness. Commit your anxieties to God and be thankful you serve the king who is now and always has been in control.

Lewis Jones has a PhD in Astrophysics and is a graduate of Moore Theological College. He works for AFES, leading The Simeon Network, a network of Christians working in academia. He is interested in apologetics, particularly the interaction of Science and Christianity, and dabbles in Liberal theory. He is a member of Randwick Presbyterian Church, where he is an elder. Lewis also is a member of the Gospel, Society and Culture Committee of the NSW Presbyterian Church.

*First published by the Gospel, Society and Culture Committee. Used with permission.

Part two is here.