Mike Frost was raised in a nominally Catholic family. He only began to show real interest in the Christian faith in his final year of high school, when students and an evangelistically-minded teacher invited him to an Inter-School Christian Fellowship group.

“I was spiritually curious,” Frost recalls, “but it wasn’t until university that I made a commitment to Christ. The grace and love and kindness of friends who wanted to share the gospel with me – that was the key.”

“It’s really lovely to grow up in a church and to slowly find faith. But that wasn’t my experience; it was a real sense of becoming a Christian – a real conversion. So it becomes part of your ‘spiritual DNA’ that your faith is a shareable thing.”

Frost discovered that he was gifted by the Holy Spirit for evangelism, eventually becoming the pastor of a church with a strong evangelistic focus. In 1999, he became the founding director of the Tinsley Institute, a mission study centre at Morling College in Sydney.

“The mission of God’s people today is to alert everyone everywhere to the fact that our God reigns in Christ.” – Mike Frost

Mission is the Shape of Water, by Mike Frost

In September 2023, Frost published his latest of twenty books, the brilliantly titled Mission is the Shape of Water. While writing other books has sometimes been “like pulling teeth”, Frost says this one “just flowed” out of a ‘History of Christian Mission’ course that he has taught at Morling College for about a decade. “I can’t think about church or ministry or personal faith,” he concludes, “without thinking of it through the lens of mission.”

Frost is quick to clarify what he means by ‘mission’, which is not only explicit attempts to convert people to the Christian faith. In the old covenant, he explains, Israel’s mission was to alert the nations to Yahweh’s reign; and in the new covenant that reign is revealed in the incarnation, life, death and resurrection of Jesus. “The mission of God’s people today,” he summarises, “is to alert everyone everywhere to the fact that our God reigns in Christ; and I can’t think about ministry other than seeing that as its ultimate end.”

Mission means more than we think

When we think of mission, we tend to think of word-based preaching and evangelism. While Frost fully affirms these ministries, he also aims in Mission is the Shape of Water to encourage a “healthy Christian memory”; to show that Christian mission has taken all sorts of shapes over the long history of the church. Part of effective mission is learning to fit our “container” like water does; not by compromising the content of our mission, but by allowing for creativity and flexibility in its shape.

“Mission is both spoken and acted,” Frost explains. “It’s demonstrated and announced.” The book is littered with stories in which mission took on unexpected shapes, dramatically revealing the character and reign of God.

“When the reign of God unfurls, it brings peace, justice, love, mercy, kindness and it brings faith.”

Frost recounts the story of Alice (Seeley) and John Harris, British Baptist missionaries to Africa in the 1890s. The couple planned to undertake conventional evangelistic mission, as we might imagine it.

Living near the Congo Basin, they began to encounter escapees from the Congo, where Leopold II, King of Belgium, had established the Congo Free State – effectively an enormous concentration camp where a private army forced people to extract rubber from the Congo Basin. When victims failed to meet their rubber quotas (*gruesome alert*), members of the private army would remove their limbs to make up the weight. “It’s one of the greatest human rights violations of the early 20th century,” Frost laments. “A lot of people don’t know about it, but it was utterly despicable.”

Before their journey, someone in London had given Alice a newfangled and rare piece of technology: a personal camera. At first, pictures were taken teaching classes of African children and baptising people in the river. But, encountering the suffering of the Congo Free State – severed limbs, drownings and, if it’s possible, worse – Alice became determined to take a camera into this hellish jungle.

After cataloguing hundreds of photos, conducting interviews and collecting stories, Alice and John toured the United States and the United Kingdom, presenting the slideshows and ultimately shaming the Belgian government into shutting down the entire operation.

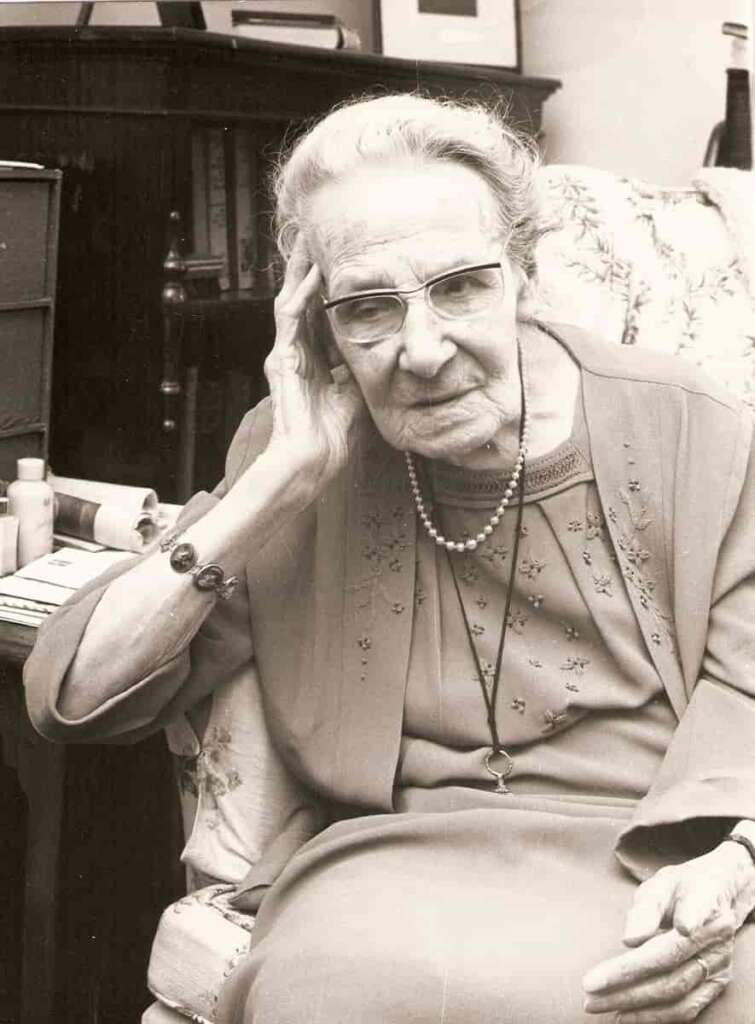

Alice Seeley Harris

As Frost summarises, “a bit of technology and a very feisty woman put in a place of utter outrage, and God uses her to free hundreds of thousands of people from abject suffering. God reshaped her ministry given the particular challenges that the Congolese were facing. The mission is always to alert people to the reign of God, but it will be shaped by the container into which it’s been poured.”

Frost recounts the story of Tony Rinaudo as another example of the unexpected form mission can take, shaped both by its context and by God’s unpredictable plans. Whether it’s ending oppression and genocide in the Congo or lifting families out of poverty in the Niger, “these are anti-kingdom things. When the reign of God unfurls, it brings peace, justice, love, mercy, kindness and it brings faith.

“Will I help to grow trees in Niger or be a preaching evangelist? I don’t think we should have to decide. Either! Both! All Christians ought to be committed to reading the context in which they find themselves in order to see what mission looks like.”

Keeping our eyes on the ball

Frost, whose book received glowing commendation from historian John Dickson, does not shy away from the uglier side of Christian history. Rather than following the undercurrent of hagiography in many books on Christian mission, he says “we need to confront the fact that missionaries have at times behaved reprehensibly; or, if not reprehensibly, have allowed themselves to be used as tools of colonialism or conquest. We have to acknowledge our own history.”

Frost acknowledges that managing the tension of letting mission be shaped by context without compromising the gospel itself is complex, but insists that we acknowledge our context while holding onto the gospel, working to reveal the Kingdom of God “as it truly is, not as I might want it to be, or the context might want it to be.”

“We need to be braver.”

Frost thinks a crucial message for the contemporary Australian church is to keep our eyes on the ball. Frost notes that Christians are sometimes swept up in “culture wars”, labelling things “essential” that our world tells us are essential, but which examination of the Christian faith renders peripheral.

“We need to be braver about resisting being shaped by the culture wars,” Frost urges. “We do want to be relevant, shaping mission to its context. And if the context is raising questions, the gospel should have something to say about those. But it seems to me that we’re getting caught up in the conflict in a really unhelpful way. We need to continue to remind ourselves of who Christ is, what the kingdom of God is about.

“If you can’t do that,” he concludes, “you can’t do mission.”