American church membership has plummeted to the record low of less than 50 per cent of the population, according to new research by Gallup. And it is not just because millennials are turning away from religion.

Instead, Gallup’s research shows a continuing decline in church membership for more than two decades – across believers of all ages.

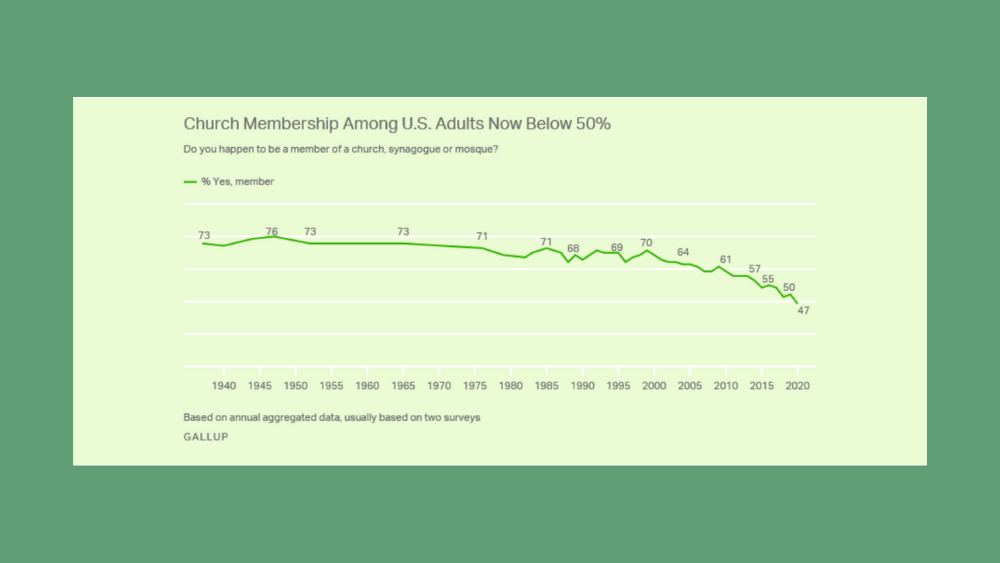

Gallup first began measuring US church membership in 1937, when it measured at a whopping 73 per cent.

That impressive membership figure continued to hold at around 70 per cent for the next 60 years. But from 1999 onwards, the number began to decline.

And, by 2008-2010, US church membership had dropped to around 62 per cent, then to around 55 per cent in 2015.

The “nones”

Coinciding with the decline is the rise of Americans who claim no religious affiliation at all, often referred to as “nones”. Gallup reports this group to be around one in five Americans (21 per cent) – making them as large a group as evangelicals or Catholics.

“As would be expected, Americans without a religious preference are highly unlikely to belong to a church, synagogue or mosque, although a small proportion – 4 percent in the 2018-2020 (survey) – say they do,” the report from Gallup states. “That figure is down from 10 per cent between 1998 and 2000.”

It’s not only Christians whose membership is declining, though, but “religious Americans” in general. Gallup reports that the overall number of “religious Americans” (around 76 per cent of the US population) who are members of a church, synagogue or mosque has dropped from 73 per cent in 1998 to 60 per cent now.

Denomination, location and education

So exactly which Christians are turning away from church membership?

There are some differences denominationally: Catholics dropped from 76 per cent to 58 per cent in the period (1998/2000 – present) – a bigger drop than Protestants, who went from 76 per cent to 64 per cent.

Where Americans live and how they vote was also measured, as was college education.

Among Republican-voting Christians, church membership dropped from 77 to 65 per cent of the population in the same time period; Democrat-voting Christians went from 71 to 46 per cent; and Independent Christian voters went from 59 to 41 per cent.

American Christians who live in the east of the country went from 69 to 44 per cent church members in that time – a massive 25 percentage-point decrease. Yet, even this huge drop of church membership by America’s eastern Christians didn’t bring them to the level of the country’s western Christians, with only 38 per cent of church members (down from 57 per cent in 1998/2000).

In contrast, US Christians living in the south and midwest of the country retained levels of church membership above 50 per cent (with 58 and 54 per cent respectively). This is despite a steady decline in the same time period, when 74 per cent of America’s southern Christians and 72 per cent of midwestern Christians were church members.

Interestingly, church membership among US Christians who are college graduates did not decline to below the 50 per cent mark, instead falling from 68 per cent to 54 per cent (1998/200 – present). US Christians who are not college graduates but who are church members, though, went from 69 per cent to 47 per cent.

Comparing traditionalists, baby boomers, generation X and millennials

On the one hand, Gallup’s research reinforces what many would expect – that each generation is becoming less religious and less inclined towards church membership.

Indeed, 66 per cent of traditionalists (US adults born before 1946) are church members – a number that decreases to just 58 per cent of baby boomers, 50 per cent of generation X and only 36 per cent of millennials. Hence, the decline in church membership certainly can be largely explained by population change, with those in older generations who were likely to be church members being replaced in the US adult population with people in younger generations who are less likely to belong.

Yet while population change can explain a large part of church membership’s decline, there is another significant factor.

In fact, Gallup’s research shows that the percentage of church members in the older US generations have themselves shown an decrease in church membership – with traditionalists dropping from 77 to 66 per cent of the population and baby boomers going from 67 to 58 per cent.

“The two major trends driving the drop in church membership – more adults with no religious preference and falling rates of church membership among people who do have a religion – are apparent in each of the generations over time,” reports Gallup.

“Since the turn of the century, there has been a near doubling in the percentage of traditionalists (from 4% to 7%), baby boomers (from 7% to 13%) and Gen Xers (11% to 20%) with no religious affiliation.”

Making sense of the data

Gallup’s own analysis puts these findings in the wider context of US religion, drawing on other research: “The US remains a religious nation, with more than seven in 10 affiliating with some type of organised religion,” it says.

“However, far fewer, now less than half, have a formal membership with a specific house of worship. While it is possible that part of the decline seen in 2020 was temporary and related to the coronavirus pandemic, continued decline in future decades seems inevitable, given the much lower levels of religiosity and church membership among younger versus older generations of adults.”

From Gallup’s perspective, the formalisation of a Christian’s faith via church membership is a key indicator of the health of the Christian church and its ongoing survival.

“Churches are only as strong as their membership and are dependent on their members for financial support and service to keep operating. Because it is unlikely that people who do not have a religious preference will become church members, the challenge for church leaders is to encourage those who do affiliate with a specific faith to become formal, and active, church members.

“While precise numbers of church closures are elusive, a conservative estimate is that thousands of US churches are closing each year.”

However, Eternity notes that church membership is not equally regarded as a key indicator by Christians across the world. Indeed, in Australia, many denominations do not even have a system of formalised church membership, nor measure it, tracking church attendance and spiritual practises instead.

Since the release of Gallup’s research, a wide range of US Christians have offered explanations for the country’s declining church members.

Conservative blog site The Gospel Coalition says the findings show that “younger people are unclear on why they need to be a ‘member’ of a church”.

“Membership implies one belongs to an exclusive group not necessarily welcoming of others. Why then would a Christian need to be a ‘member’ of a church?” author Joe Carter writes.

Carter goes on to argue that “church membership is all about a church taking specific responsibility for you, and you for the church” and “is necessary because it helps us obey essential commands found in Scripture”.

The Washington Post’s Sarah Pulliam Bailey provides insight in a similar vein, quoting said Ryan Burge, an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and a pastor in the American Baptist Church, who notes that for some Americans, religious membership is seen as a relic of an older generation.

Burge, who recently published a book about disaffiliating Americans called The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going, predicts that in the next 30 years, the United States will not have one dominant religion.

“We have to start thinking about what the world looks like in terms of politics, policy, social service,” Burge said. “How do we feed the hungry, clothe the naked when Christians are half of what it was. Who picks up the slack, especially if the government isn’t going to?”

Pullliam Bailey also cites the thoughts of Tara Isabella Burton, author of Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, who points to two relevant trends amongst young people: a broad distrust of institutions, and the “celebration of ownership” that sees them curating their own experience by mixing parts of different religions – the result of “a different kind of relationship with information, texts and hierarchy” for those who have grown up in the internet age.

Equally interesting are the thoughts of Kate Murphy, pastor of The Grove Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, whose opinion piece ran in The Charlotte Observer.

“The party line is to blame ‘this generation’ for being less faithful, or ‘the media’ for corrupting hearts or ‘the government’ for taking prayer out of school. Once we’ve finished blaming those outside our communities, we turn to those inside and pressure them to give more, work more, sacrifice more to reverse the trend. But I don’t think any of that is a faithful response,” writes Murphy.

“Because, while church membership is declining, people are still as hungry for the things of God as they ever have been. People are still seeking justice, forgiveness, hope, love and belonging … So the problem isn’t with those outside the church, and it certainly isn’t with God. The problem — and it is a problem — is with us. The problem is that most of the church in America looks more like America than the body of Christ,” she goes on.

“I love the church. But I love Jesus more, and the church has done a terrible job being faithful to the way of Jesus. When we who love the church see these numbers, we shouldn’t kid ourselves. People aren’t rejecting Jesus — they are turning away from churches that represent him badly. Churches that are full of programs instead of prayer, full of doctrine but empty of mercy. Turning away from church that lies is the first step towards the truth.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?